January 31, 2022

by Stephanie Crawford

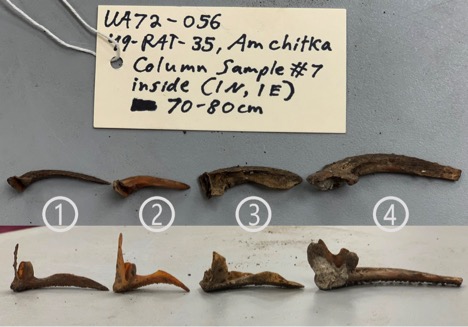

Close up of bones collected at midden sites in the Aleutian Islands. Most of the bones seen are remains from various fish species.

Today, my work brought me to the University of Alaska’s Museum of the North. Normally in my position as a Research Professional at UAF, you can find me in my office organizing data files into our many databases, snipping pinniped whiskers into tiny 1 mm segments for stable isotope analysis, or occasionally in our laboratory analyzing samples for mercury content.

Today, I got to be a kid again. I looked at trays piled high with bones, shells, and other hard parts that had been collected from archaeological sites in the Aleutian Islands in the 1960s and 1970s.

What fun it was to wonder. What am I looking at? How do these fit together? Our PI Nicole Misarti, found a cod premaxilla in her pile to show me an example of what I was hunting for.

Right premaxilla from a Pacific cod, Aleutian Islands. The top photo shows the dorsomedial surface (top view of the portion facing the inside of the mouth), while the bottom photo shows the ventral (bottom) surface.

I am pretty good at picking up on search images—years of surveying for wildlife and documenting behavior has honed that skill. I quickly learned what portion of the premaxilla looked distinct from the other bones and fragments, and I found several fish premaxillas. I showed each to Nicole as I found them: “Yep, premaxilla. Wrong species.” As deflating as not finding the “right” species might be, it was still rewarding to know I was finding the correct bone. As you may imagine, we are all quite competitive in our search endeavors. Bragging rights were self-proclaimed by some, though no tiaras were donned by the Cod Queens.

Bone piles? The bones we sifted through in the comfort of a museum basement laboratory originally were part of middens (essentially garbage piles) left behind by Unangax^ many years ago. Think about how much you can learn about someone today simply by examining their trash. You could determine where they shop, what they eat, if they have children or pets, or maybe even what kind of job they have. The same holds for ancient peoples. We certainly can learn much about what was eaten or used as tools or for clothing, shelter, or transportation. For our project, the bones themselves hold the story of the patterns of mercury deposition and uptake in the Aleutian Islands region. Excavations at archaeological sites are conducted very methodically and documented with great detail. We examined bones collected from between 0-10 cm depth at a particular site, and then 10-20, 20-30, 30-40 cm and so on from the same site, traveling back in time farther and farther as the samples came from deeper and deeper sections.

Now, what is a premaxilla bone? Many have heard the terms maxilla (fixed-position upper jaw bone) and mandible (movable lower jaw) in relation to our teeth function. The prefix pre- means before or in front of; therefore, the premaxilla is a bone in front of the maxilla bone. All vertebrates have them, but we don’t often hear about this bone in everyday life.

Why the premaxilla? From my brief time sorting through bones, I see several reasons.

1) They are typically sturdy enough that they aren’t badly broken.

2) You can pretty easily distinguish species by prominent features of the premaxilla.

Comparison of right premaxilla bones from Pacific cod (#4) and three other species of kelp forest fish that are commonly found in the archaeological sites of the Aleutians. The top photo shows the dorsal (top) surface of each bone. Note the readily observable differences in shape. Bone 3 has a distinct recessed cup. In the bottom photo, you can compare the profile of each bone looking at the medial surface (portion facing the inside of mouth). The variability is tremendous among the species, particularly in the spike and shape of the left edge of each bone shown and the arch along the bone as you move mid-bone to towards the right end.

3) You can, once you understand where the bone fits in the skull, easily differentiate between the right and left premaxilla.

Graduate student Mary Keenan demonstrates how it helps to pretend to “be the cod” to determine if you have a right or left premaxilla in hand.

4) If you obtain precise measurements of the premaxilla using calipers, you can accurately estimate the size of the entire fish.

Once the cod premaxillas have been identified from a bone pile, you can sort them further in to groups of right and left premaxillas. Then, you can use the size of the premaxilla to ensure that you are only sampling one bone from each individual cod – deductively, two small left premaxillas and one large right premaxilla must represent 3 individual fish. Doing this over and over again from discrete parts of the archaeological sites allowed us to collect 67 individual cod premaxillas last week. Think about that – amongst thousands and thousands of bones, 79 hours of sifting through bones, and various amounts of help from 6 different people, we found 67 individual bones to add to our research project.

While the objective was to find the cod premaxillas, as well as any bones of Otariids found in the region (eared seals: northern fur seal, Steller sea lion), this entire process revealed much more. Some piles were more shell than bone – pieces of urchin tests (skeletons) and limpet shells were easily identifiable.

Variability amongst different piles we sifted through. The left most photo is mostly mollusk shells, the middle mostly mammalian bones, and the right is mostly fish bones among ash.

I even found an auklet (small seabird) bone (identified by PI Caroline Funk) in one batch—bird bones stood out from the bulk of the fish bones to me. Fish bones were sort of yellow-brown, while the bird bones were lighter in color, almost white. Bird bones were also much lighter than mammal bones due to their low density. Even with little knowledge about fish, mammal, and bird bones, you can fairly easily sort between these broad groups. PI Nicole Misarti found a raptor beak and PI Caroline Funk showed us a piece of bone carved as part of an Unangax^ baidarka (kayak) lashing.

Beak from raptor (bird of prey) on the left. Right photo is a bone carved to be part of an Unangax^ baidarka (kayak) lashing.

My role in this project is to maintain all the data regarding these samples. This includes the detailed site information and carbon dating information used to determine how many years ago these fish were used by Unangax^. Since I have no prior archaeological experience, this opportunity to observe the museum specimen retrieval process will help me understand how all the different numbers I receive pertain to a specific bone. We assign a unique project ID to each sample, but there have also been field IDs, site IDs, individual bone catalog numbers, numbers associated with the carbon dating process, and so on. If ALL these numbers are stored in an organized cross-reference relational fashion, I should be able to use the database to quickly answer a PI’s question such as, “how many individual cod from X site and Y time range before present do we have both mercury and stable isotope data for?” in just a matter of seconds.

What next? Small pieces of each bone will be chiseled off. Some pieces will have collagen extracted; the collagen will be analyzed at the Alaska Stable Isotope Facility for carbon and nitrogen (stable isotope data go in the database). Other small chunks of each bone will be homogenized (ground) into a powder and analyzed for mercury content (mercury data also go in the database) in our laboratory.

Significance

Our research group’s prior work revealed mercury concentrations of concerning levels (potential for adverse effects) in portions of the Aleutian Islands, particularly in live free-ranging Steller sea lion pups sampled this century. This project will help us answer questions about the presence of mercury in the Aleutians over the past 3000 years, before and after the Industrial Revolution, and around timing of certain volcanic eruptions—which should in turn help us answer the question everyone asks—where is the mercury coming from?